The History of Samaná: Where Freedom Anchored and Empires Dreamed

Long before it became a haven for eco-tourists and whale watchers, the Samaná Peninsula was something else entirely – a place where history collided, cultures converged, and liberty found an unlikely refuge. This is the story of a land once seen as an island, coveted by empires, and shaped by the dreams of freedom seekers.

A Land First Loved and Resisted: The Taíno Era

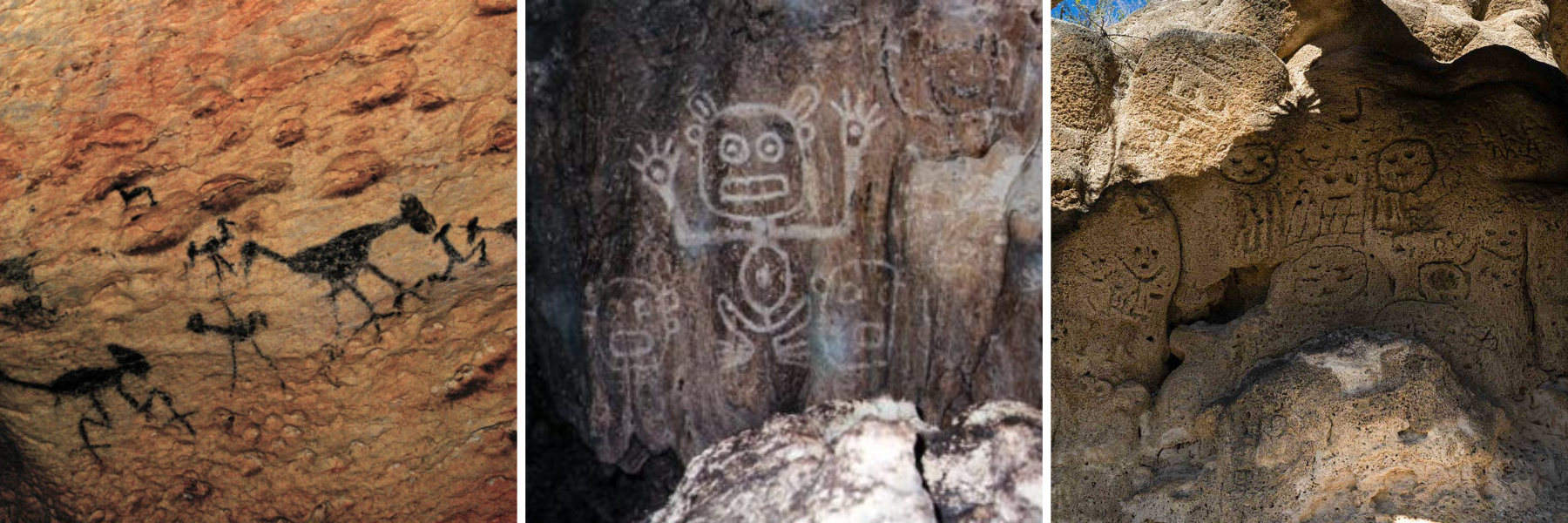

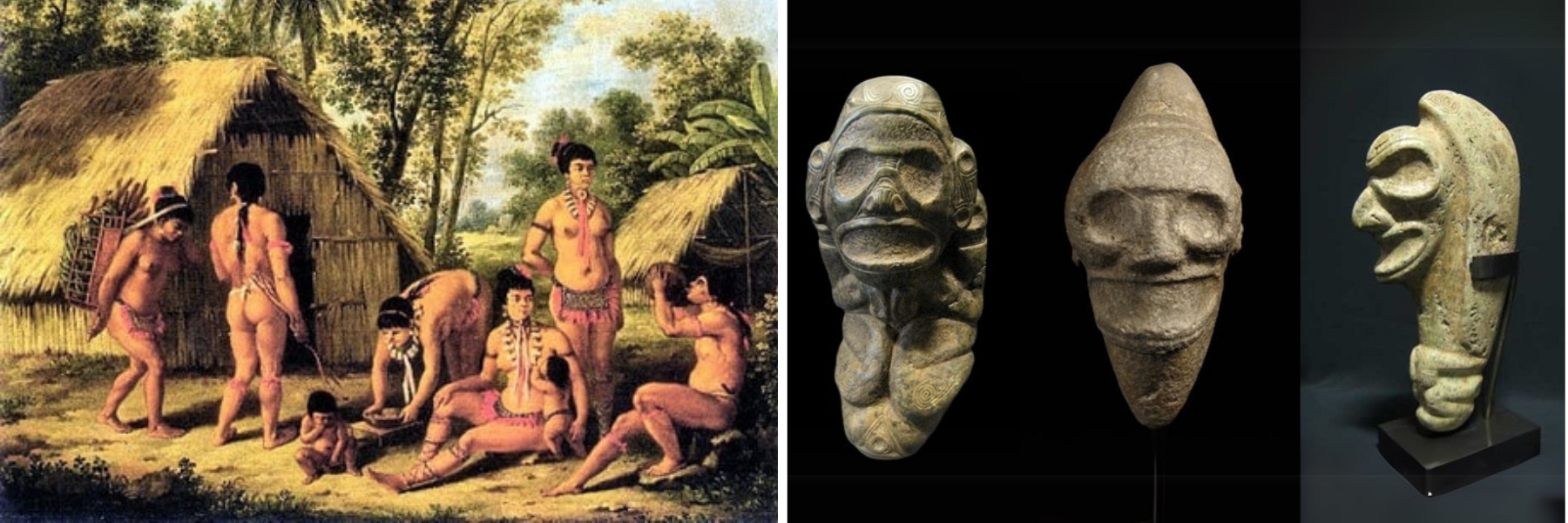

Long before any foreign sails touched the horizon, the Samaná Peninsula – known in early colonial records as “Xamaná” – was home to the Ciguayos – a distinct subgroup of the Taíno people, with a fiercely independent spirit, a unique language, and a reputation for their skill with bows and arrows. Their cultural connection to the sea and the land shaped their identity, evidenced in the petroglyphs that still line the caves of Los Haitises.

When Columbus sailed into Samaná Bay in January 1493, he was awestruck by the land, calling it “the fairest land on the face of the earth.” But the meeting was no Edenic exchange – instead, it erupted into the first armed resistance by Indigenous people against European colonizers in the Americas. The Ciguayos met the intruders with a shower of arrows, earning the bay the name “Bay of Arrows.”

This was not just a historical footnote – it was a defining moment that set the tone for Samaná’s defiant spirit. The legacy of the Taíno, though later overshadowed by colonization, survives in place names, oral traditions, and sacred caves etched with ancient visions of marine life, deities, and nature.

Colonial Chess and the Making of Santa Bárbara

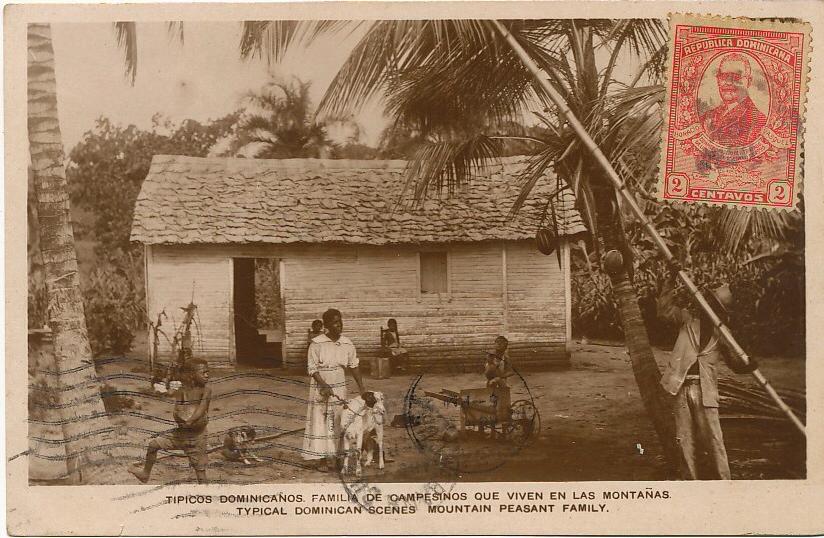

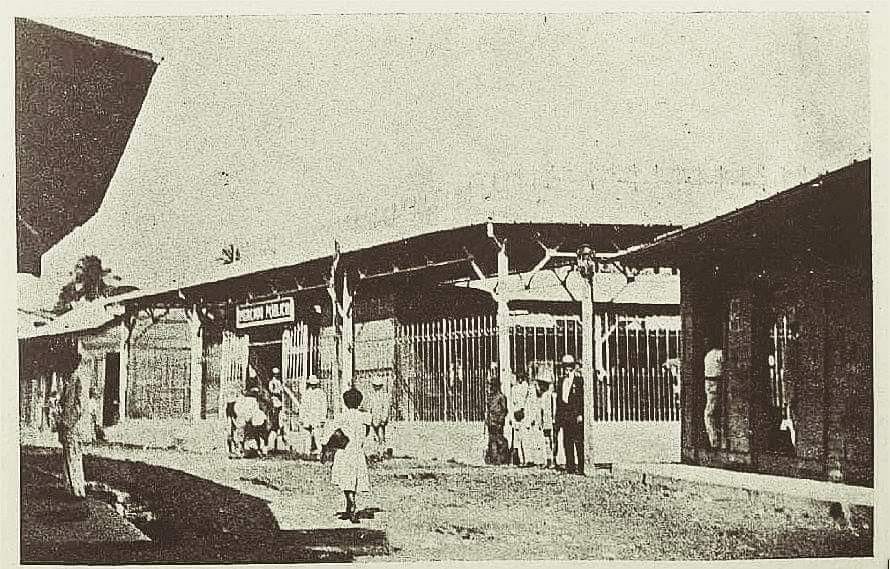

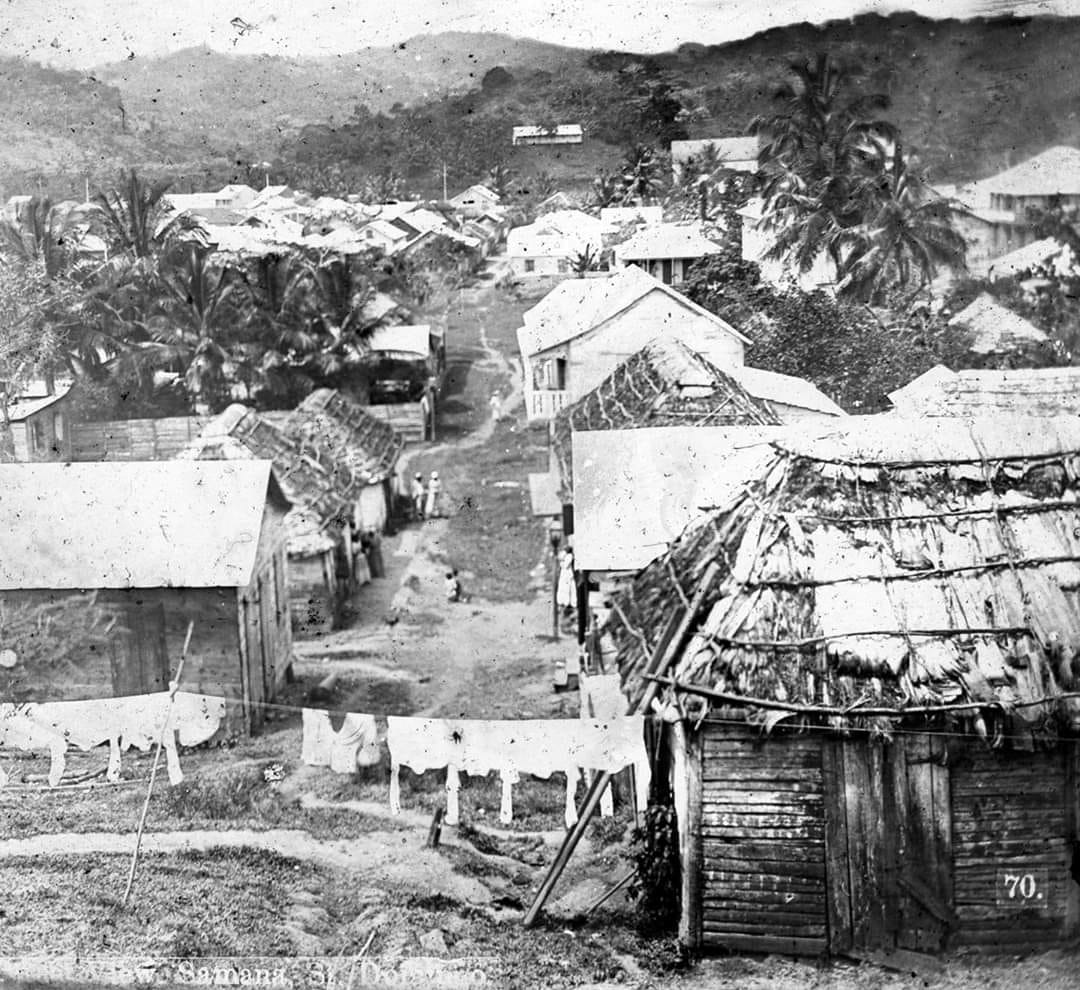

Though claimed early by Spain, Samaná remained a marginal and rebellious edge of empire. Pirates found shelter in its hidden coves, maroons (escaped slaves) lived in its forests, and European powers eyed its deep bay with envy. In 1756, to defend their claim, Spanish authorities founded the town of Santa Bárbara de Samaná, populating it with Canary Islander settlers.

This was more than a simple village; it was a calculated geopolitical move. Spain was trying to outpace rival claims from France and Britain by cementing a civilian presence. But despite its strategic port, the town grew slowly. Even by the 1780s, it housed barely over 200 residents.

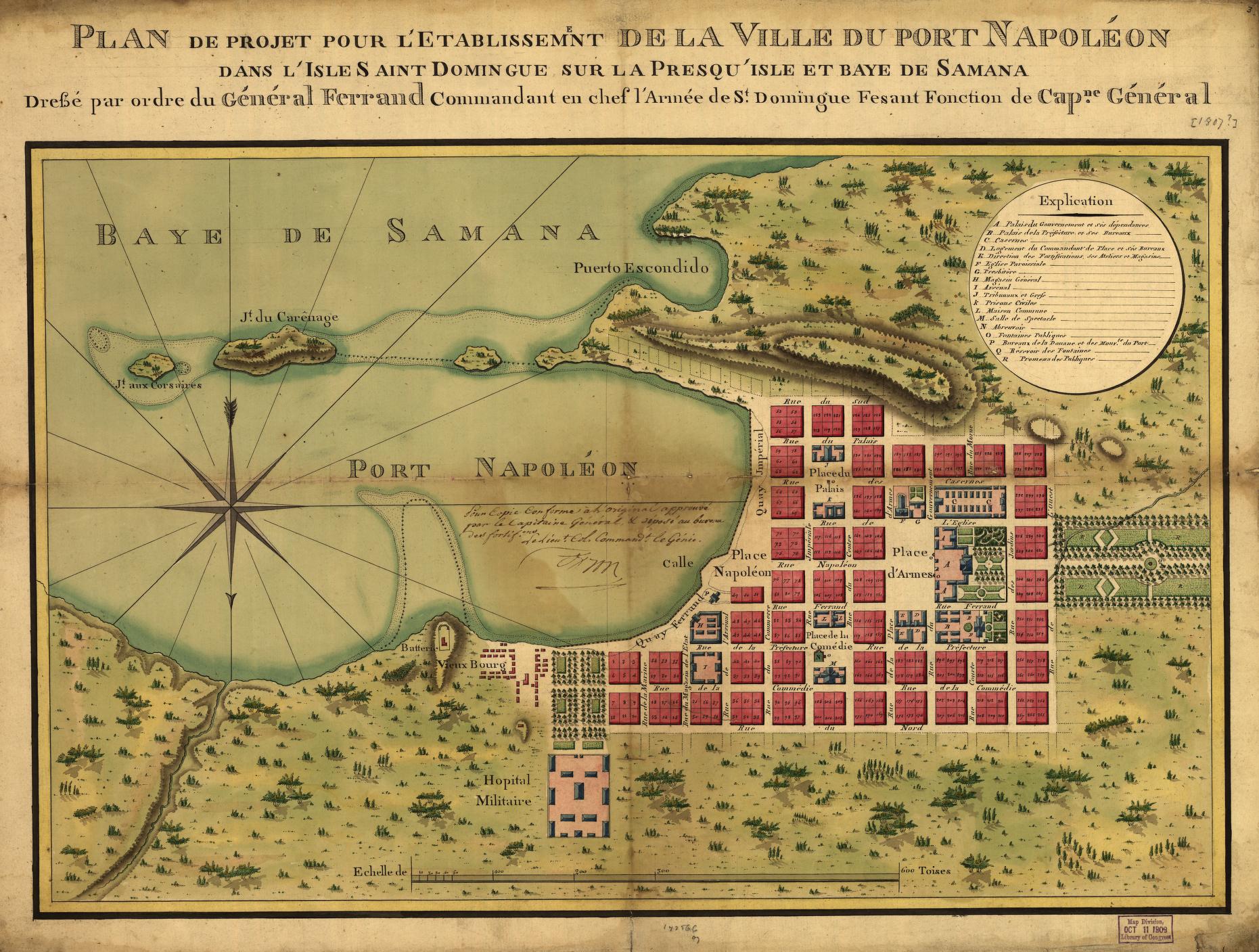

Then came 1795. Spain ceded Santo Domingo to France under the Treaty of Basel. The French, under Napoleon, had imperial ambitions: they reimagined Santa Bárbara as “Port Napoléon” and drafted elaborate maps with planned fortresses and boulevards. Although these dreams were never realized, the very attempt illustrates just how important Samaná had become in the colonial imagination.

Samaná’s Haitian Chapter and the African American Exodus

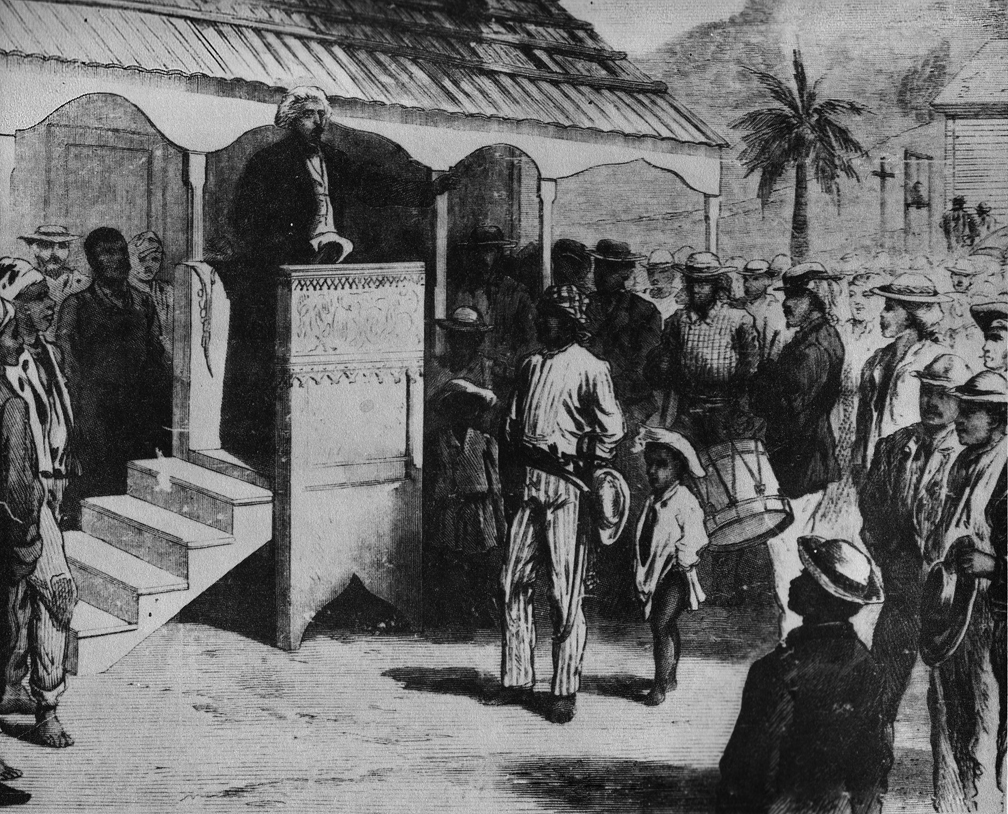

The early 19th century brought sweeping changes. In 1822, after Haiti reunited the island, President Jean-Pierre Boyer abolished slavery across the former Spanish colony. He viewed Samaná not only as a naval stronghold – evidenced by the construction of forts at Los Cacaos and El Limón – but as a safe haven for Black freedom.

That same year, Boyer extended an invitation to free African Americans in the United States to immigrate to Hispaniola. Facing increasing racism and restricted rights in the antebellum North, many Black families saw the Caribbean as a land of promise. In 1824–25, thousands sailed to Haiti, and about 200 settled in Samaná.

These families, mostly from the U.S. East Coast, brought their language, Protestant faiths, and customs with them. They built a community that was, in many ways, culturally autonomous. The Methodist and Wesleyan churches they established became the heart of social life, and their harvest celebrations and gospel singing created a rhythm of cultural pride that persists even today.

They were not temporary settlers. Unlike other Black emigrant communities in the Caribbean, the “Samaná Americans” stayed, intermarried, and contributed to the Dominican Republic’s early development. They are considered one of the peninsula’s founding cultures, having arrived before the nation’s birth in 1844.

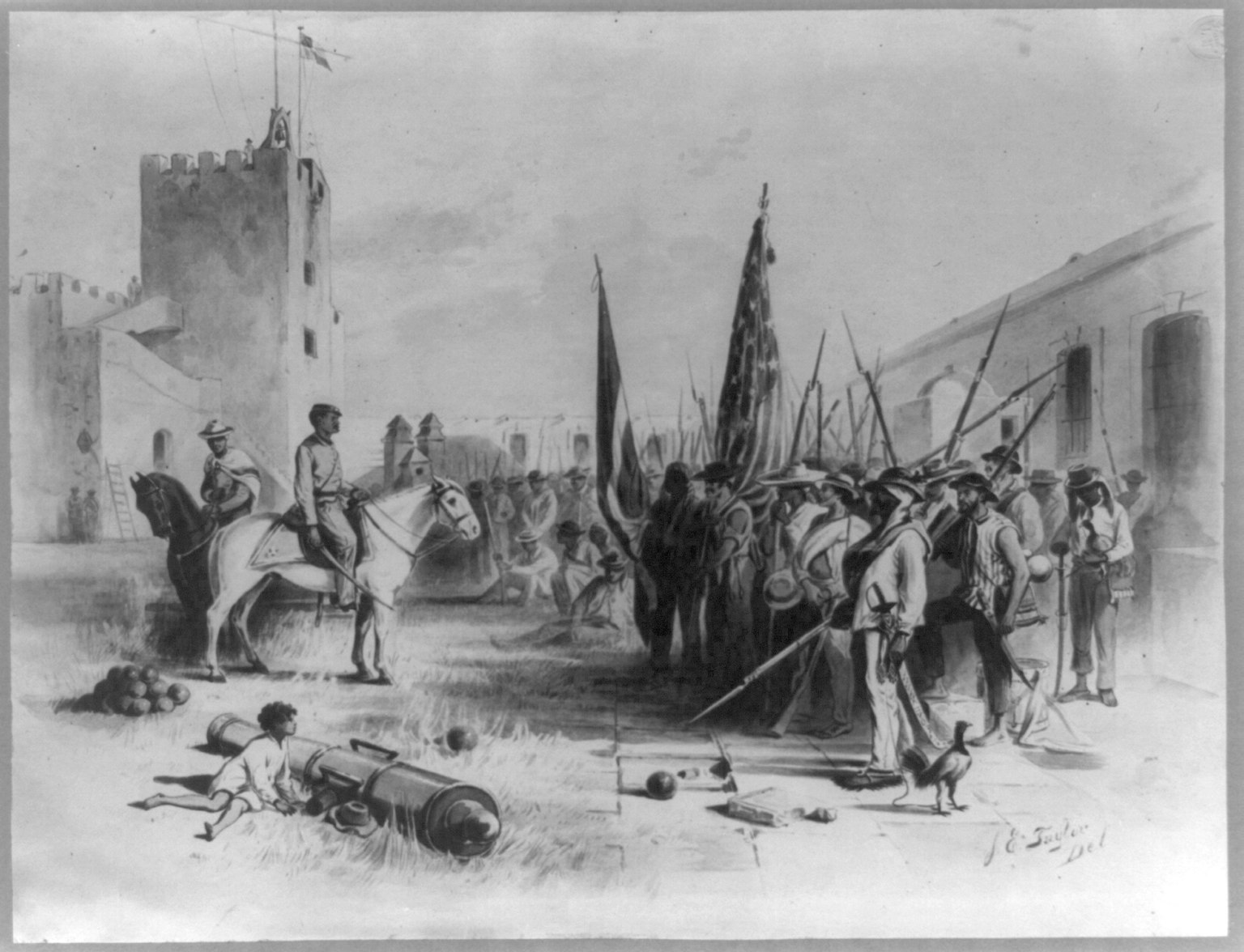

A Bay Worth Fighting For: 19th-Century Power Plays

Samaná’s significance grew in the eyes of world powers. Spain tried to reclaim it. France had fantasized about it. And now the United States came with naval aspirations. The Dominican government, fragile and frequently bankrupt, saw in Samaná a bargaining chip for protection.

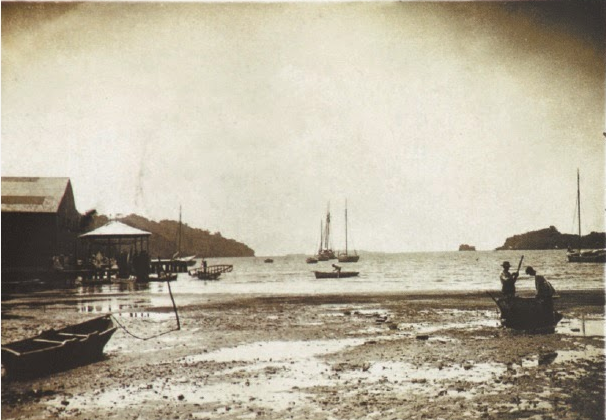

In 1871, U.S. President Ulysses S. Grant sent a commission to study annexing the Dominican Republic. They focused intensely on Samaná Bay. Its depth, natural shelter, and location along Caribbean trade routes made it the ideal naval base. Botanists studied its flora. Cartographers surveyed its coast. Politicians debated its future.

Though the annexation plan failed in the U.S. Senate, it revealed Samaná’s global importance. And once again, the peninsula escaped foreign rule – thanks, in part, to local resistance and shifting geopolitical tides.

The Long Sleep and the Slow Awakening

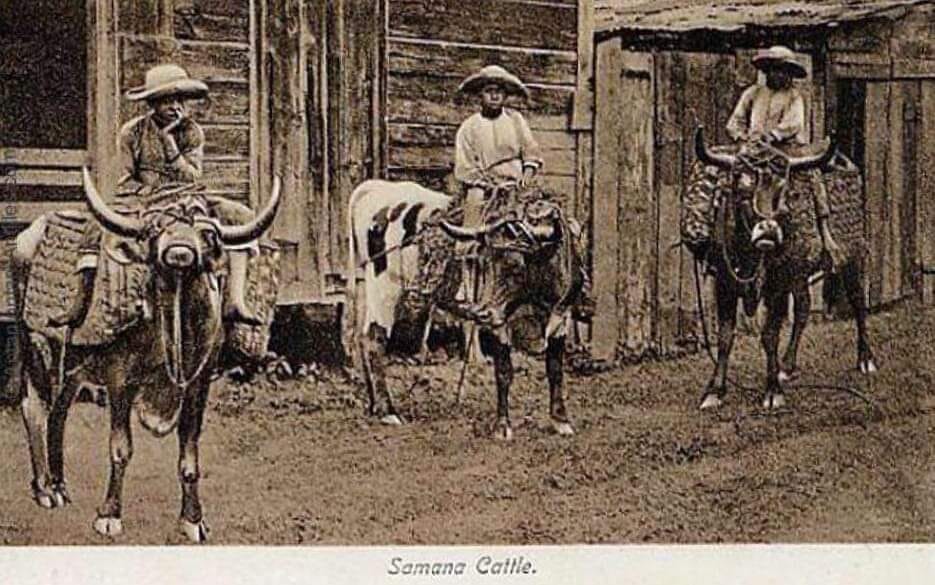

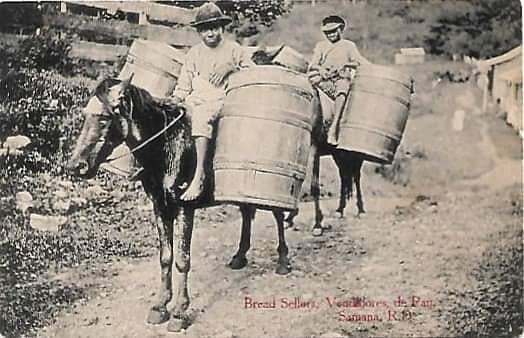

Despite its strategic value, Samaná slipped into a long period of isolation. Its rugged geography – steep mountains and thick forests – made road-building nearly impossible. Until the mid-20th century, most trade and travel happened by boat. One exception was the port of Sánchez, which briefly flourished after an 1888 railway connected it to La Vega. Coffee, cacao, and tobacco passed through en route to international markets.

But the rest of the peninsula remained quiet. This preserved Samaná’s cultural uniqueness but also left it underdeveloped. During Rafael Trujillo’s dictatorship, the region’s English-speaking, Afro-Protestant communities were targeted for being “un-Dominican.” Schools were closed, churches were monitored, and in the 1940s, fires mysteriously destroyed vital historical records – acts some attribute to Trujillo’s nationalist policies.

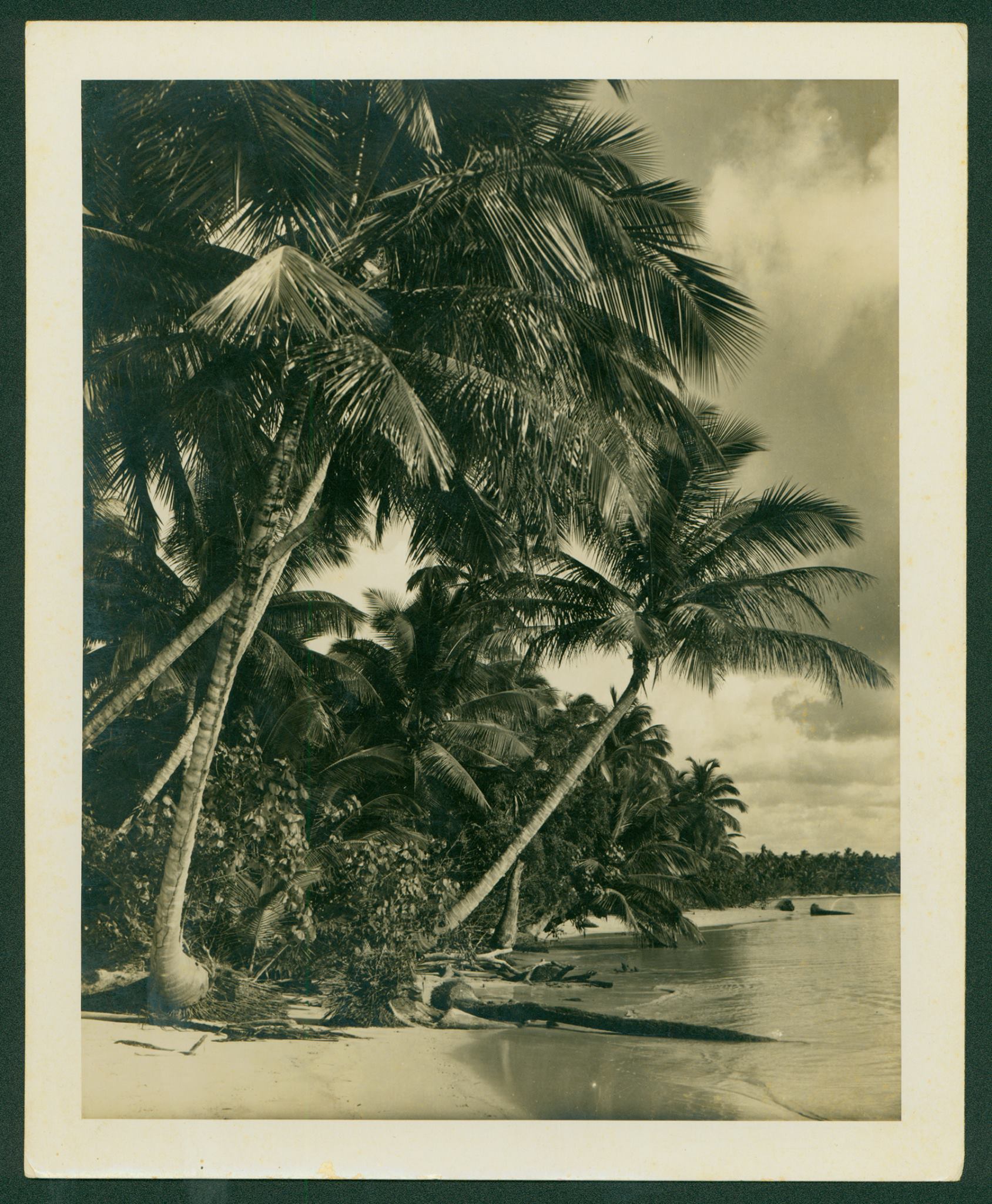

It wasn’t until the 1970s that serious infrastructure began to reach the peninsula. And with the 2008 completion of the DR-7 highway – reducing travel from Santo Domingo to just 90 minutes – Samaná finally opened to the rest of the world. Yet, paradoxically, it is precisely this prolonged isolation that preserved Samaná’s most precious qualities. While other parts of the Dominican Republic saw rapid development, Samaná remained protected by its geography. Its mountains, mangroves, and coastlines shielded its ecosystems from exploitation, allowing nature to remain lush, untouched, and astonishingly biodiverse.

To glimpse what life looked like during this quiet, pivotal era, watch the archival footage below – a rare window into Samaná in the 1970s.

Not Quite an Island: The Geography That Shaped a Myth

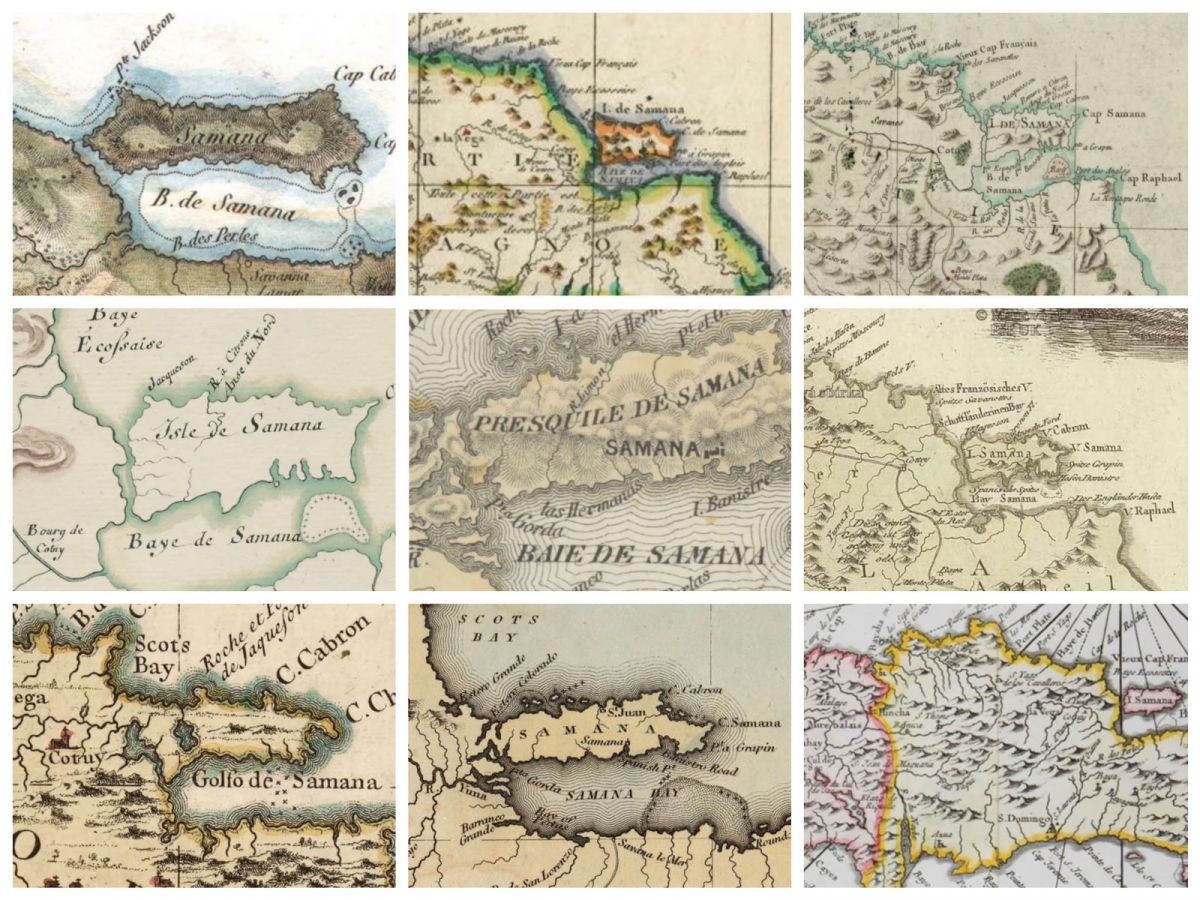

Some old maps show Samaná as an island. And for good reason. Until the mid-1800s, a wide channel separated it from the mainland. French cartographers called it the “Presqu’île de Samaná” – the almost island. Pirates once used the channel to bypass rough seas. Over centuries, the rivers Yuna and others deposited enough sediment to close the gap.

Today, as you descend from the hills into the flatlands near Sánchez, you’re crossing what was once open sea. And if sea levels rise, Samaná may yet return to its island form

Today: A Place Rooted in Memory and Motion

Samaná today is a rare balance: both bustling and quiet, global and deeply local. It is a place where tourism meets tradition. Thousands come to see the humpback whales each year, unaware that these very same migrations were once carved into cave walls by Taíno hands. Las Terrenas buzzes with French, Italian, and English, but in nearby villages, elders still speak Samaná English and attend Protestant services in 19th-century churches.

The local cuisine is a mirror of its history: American-inspired desserts with Taíno roots and Caribbean spice, hoecakes and bread puddings from antebellum America, and rich coconut-based dishes like pescado con coco that reflect the African and island culinary blending. Fall harvest festivals continue, where call-and-response gospel meets Dominican hospitality.

Above all, Samaná is a place that remembers. Its people hold tightly to their heritage while navigating the tides of modern development. They welcome visitors, but never forget who they are.

We invite you to browse a special gallery of beautiful archival photographs, offering rare glimpses into Samaná’s past. These images come from the IMÁGENES DE NUESTRA HISTORIA profile.